EIA’s assumptions short-change clean energy, and are frequently wrong

Every year, energy nerds breathlessly await the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA’s) Annual Energy Outlook (AEO). As my previous post explained, the AEO is critical because U.S. utilities, as well as global analysts and other governments, depend on the AEO’s forecasts in planning for electric and gas generation, oil supplies, oil and gas production, and a host of other projections.

While the future always has at least a few curve balls, clean energy experts couldn’t understand why the EIA’s wind and solar (both solar thermal electric and photovoltaic or PV) estimates were always so low, and the costs were so out-of-date. So they got together and wrote a letter to the EIA.

It took two years to get a response.

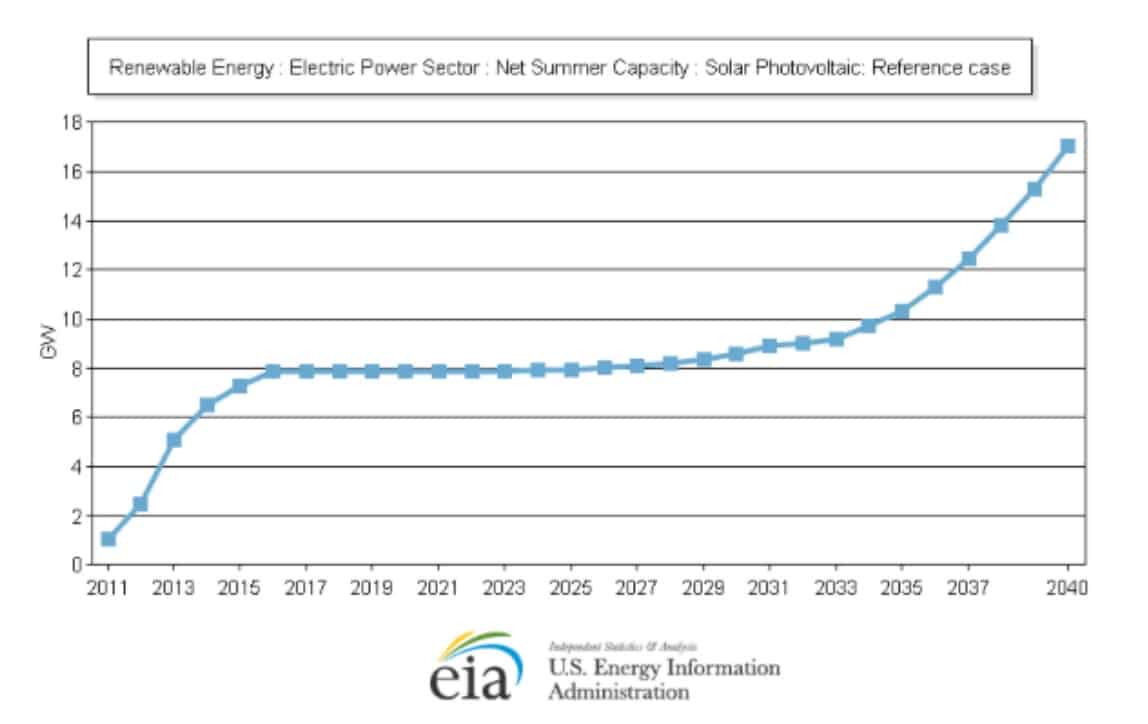

The EIA consistently — and egregiously — underestimated the amount of clean energy that would be installed. For example, solar PV installations were modeled as ending in 2016, as if no solar PV would be installed for the next 12 years, despite solar PV’s explosive growth. EIA’s solar forecasts have sometimes been wrong by 20,000%.

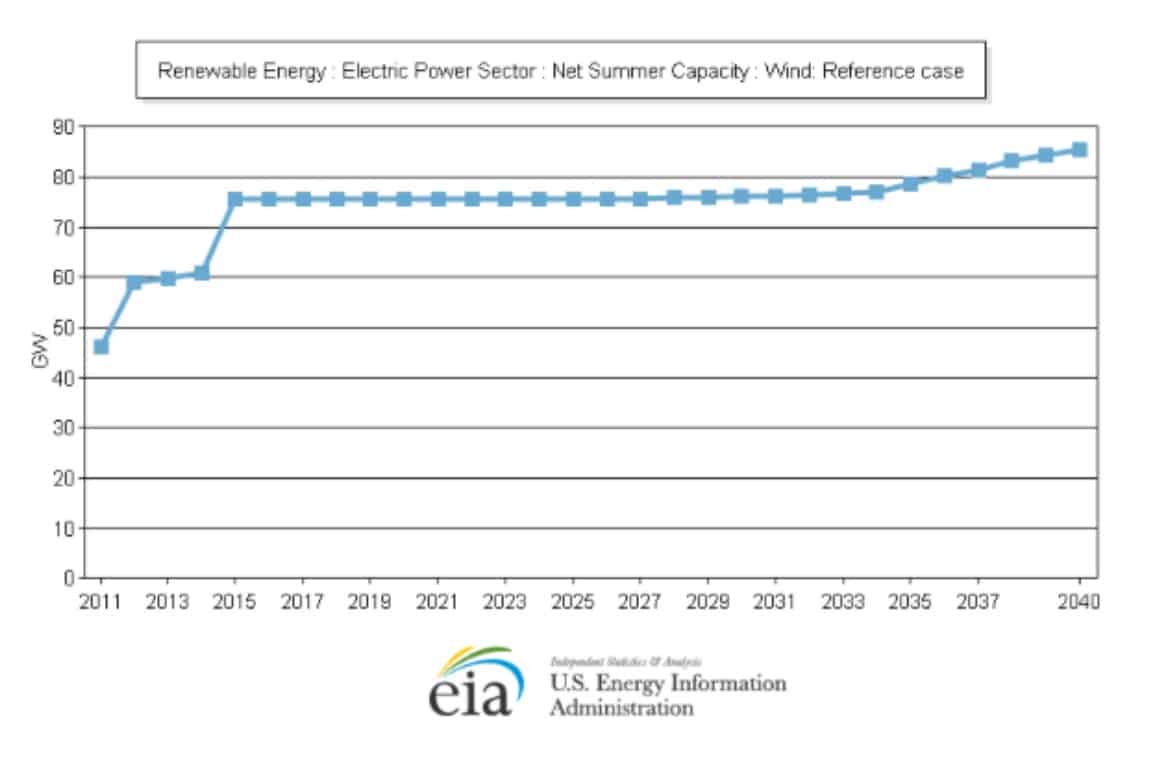

The EIA treated wind similarly, with no more new wind after 2016, and none for the next 20 years, and just a fraction of the current growth starting around 2037.

Experts also pointed out that the EIA was way off on the costs of clean energy.

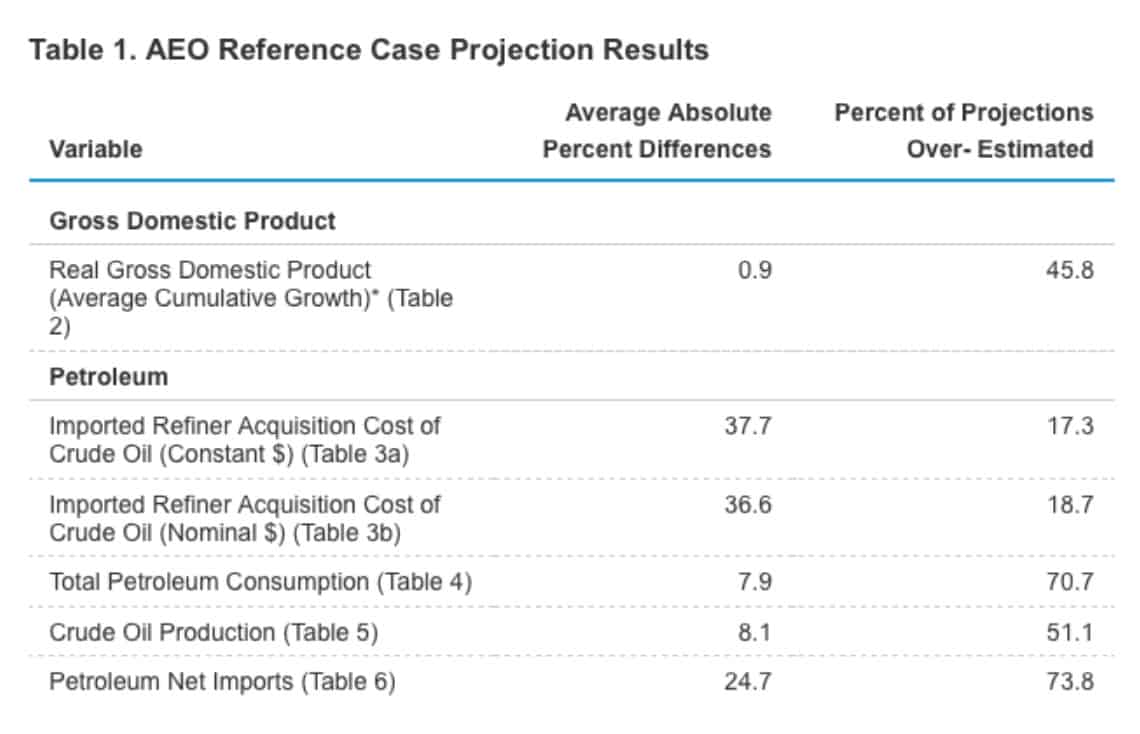

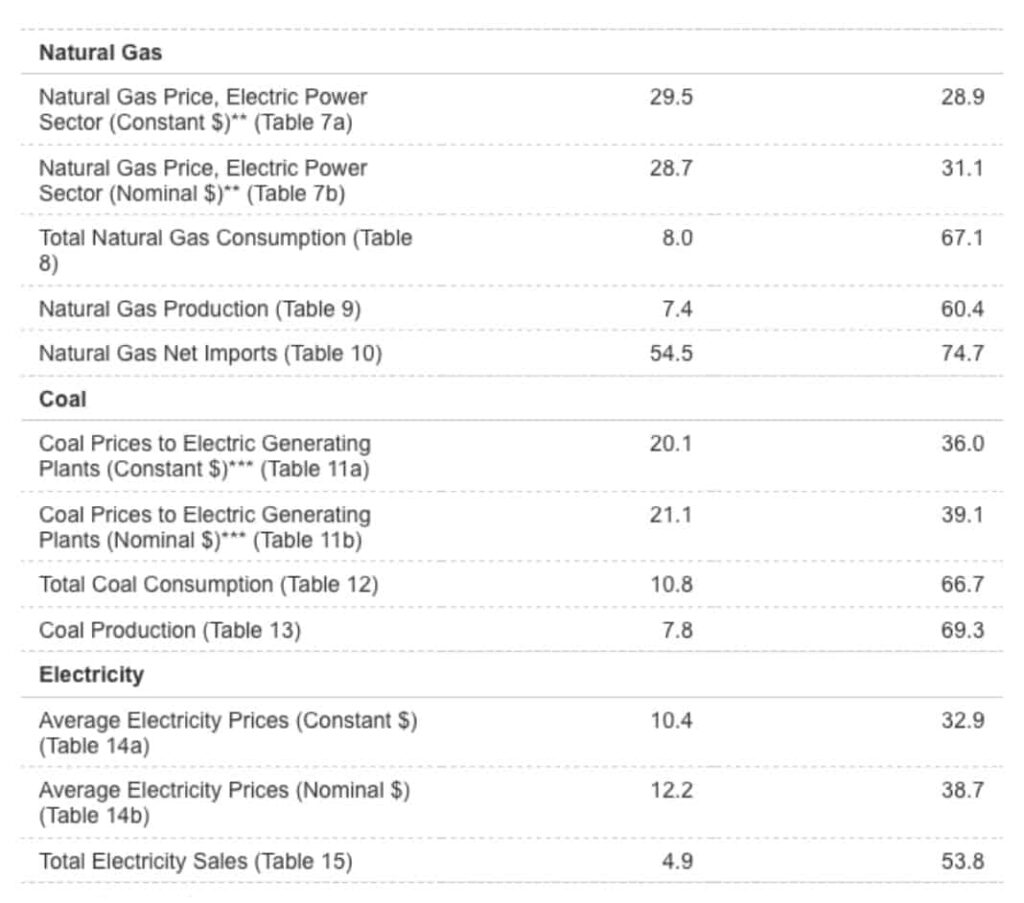

Clean energy isn’t the only place where EIA’s forecasts were off. To the agency’s credit, they have a webpage where they track the accuracy of its previous AEOs.

The chart below shows that on petroleum consumption, EIA had overestimated 70.7% of the time, while on natural gas consumption they were off 67% of the time, and on electricity sales, they were off 53% of the time.

Experts are increasingly skeptical of the EIA’s predictions. Tad Patzek, the director of petroleum engineering at the University of Texas at Austin, received some blow-back when he criticized EIA’s shale gas projections, writing in the journal Nature that assessments of shale were setting up U.S. policymakers “for a major fiasco.”

In response, the EIA questioned Patzek’s role in the research supporting the article, saying he had only a limited role in the actual studies, and accusing him of being a “major figure” in the peak oil community.

As Yogi Berra said, “it’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” It’s possible the EIA could be accurate in its predictions that gas production will continue to rise, and prices will stay low, despite some evidence to the contrary.

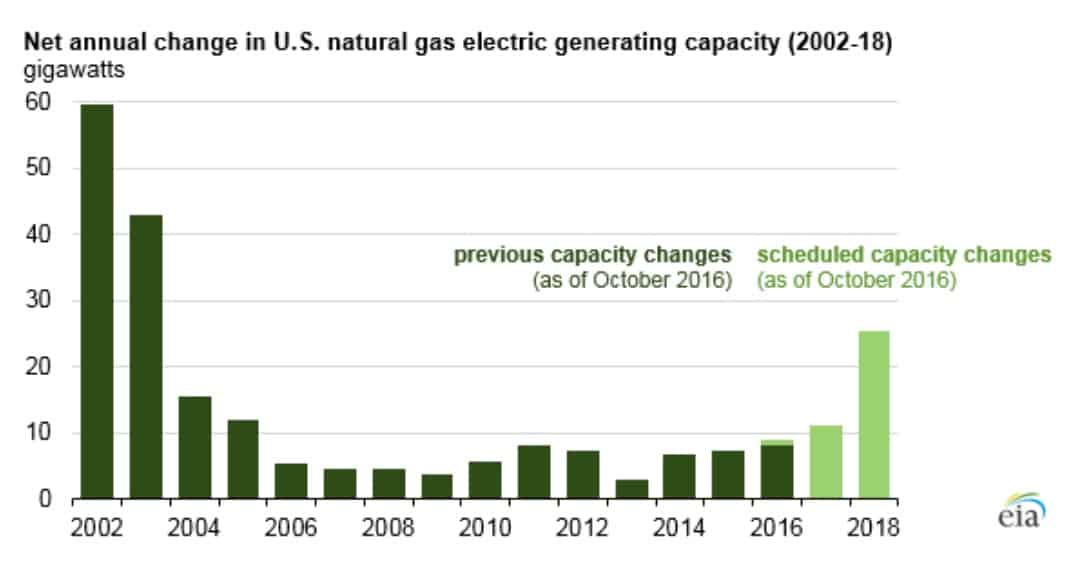

Clearly, there’s a lot at stake, with utilities planning a stunning 10 GW of new natural gas plants for 2017, and another 25 GW in 2018.

To date, the financial and energy communities have marched to the beat of a single drum when it comes to gas forecasts – ever-increasing production, and low prices as far as the eye can see. The EIA’s forecasts have been a key element of keeping that beat. With all that money and greenhouse gas emissions on the line, and given EIA’s abysmal track record at other projections, we’d benefit from many eyeballs combing through this important data, and perhaps a more diverse range of perspectives.